John Beverley Nichols was an English writer, playwright and public speaker. He wrote more than 60 books and plays. Born: 9 September 1898, in Bower Ashton, Bristol.

Is there some cosmic plan to my choice of books to review? I only recently finished my review of “Life in a gardener’s Bothy” – a bottom up exploration of life for the working classes in a variety of large stately garden bothy’s … and here I am, reading a top down perspective on gardening in a much smaller space, at least that’s how it felt initially. The first 50 or so pages set the scene for a completely different tale.

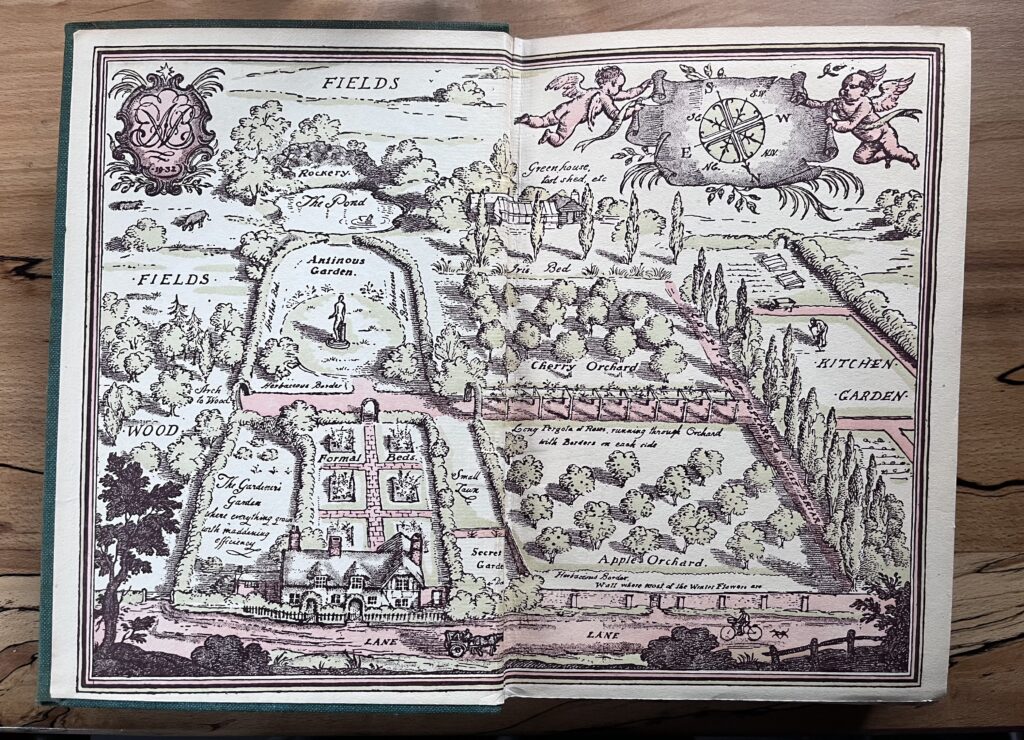

To begin with, the book does what it says on the tin … it takes you down the garden path. Not in the sense of being tricked or deceived, but in the sense of a stroll in and around a garden in development. It is also about the transformation of an individual knowing little or nothing about the process of gardening, into an individual with a better than average understanding of the structure, content, and the evolution of gardens.

The introduction does everything I want an introduction to do. It’s short. I sometimes baulk at introductions that stretch to 10-15 pages (or more). I appreciate the need to set the scene but let’s face it, if you buy a book, you want to get into the book. Clearly context is important but let’s not get carried away, eh? This one is short and succinctly disabuses the reader of any preconceived notions of what’s to come. It’s not a traditional “gardening book”, it’s not an instructional manual, it’s a soap opera punctuated with snippets of reasonably well-informed gardenalia, undisguised prejudices, whimsicalities, and flights of fancy.

The introduction does everything I want an introduction to do. It’s short. I sometimes baulk at introductions that stretch to 10-15 pages (or more). I appreciate the need to set the scene but let’s face it, if you buy a book, you want to get into the book. Clearly context is important but let’s not get carried away, eh? This one is short and succinctly disabuses the reader of any preconceived notions of what’s to come. It’s not a traditional “gardening book”, it’s not an instructional manual, it’s a soap opera punctuated with snippets of reasonably well-informed gardenalia, undisguised prejudices, whimsicalities, and flights of fancy.

I admit to being seduced to some extent by the author’s style of writing. I was transported into a time past, a time of Wodehouse’s Jeeves and Wooster, of Wilde’s Dorian Gray, a time when the class system was in full play. The writing is playful, witty and charmingly effusive. Early in the book, Nichols describes his early encounter with the incumbent gardener/caretaker … “At last, there is a sign of life. A creaking door. Streak of light. Arthur appears in a dressing gown. A dressing gown which looks as though it should have been worn by an emaciated gigolo on one of his least successful weekends.” P29

I couldn’t help but imagine who might play the author in a TV adaptation … Fry? Lawrie? For what it’s worth, the plot and characters in the book would translate into a fine, quirky, quintessentially British comedy series.

Nichols’ passion and enthusiasm for flowers is evident throughout the book. He treats  them with reverence & invites us to “make their acquaintance. “The Hamamelis Mollis : was there ever such bravery, such delicious effrontery, as is displayed, on many quiet walls throughout England, by the witch hazel in midwinter” p66

them with reverence & invites us to “make their acquaintance. “The Hamamelis Mollis : was there ever such bravery, such delicious effrontery, as is displayed, on many quiet walls throughout England, by the witch hazel in midwinter” p66

“Long experience has taught me that people who do not like geraniums have something morally unsound about them … Never trust a man or a woman who is not passionately devoted to geraniums.”

If you choose to read this book, Nichols’ views on “Women Gardeners” are likely to prove the most challenging. Some might say he’s simply being an agent provocateur, looking for laughs, or deliberately courting the prevailing patriarchy of the time. Either/all could be true but my sense is that the latter is the most likely. However you see it, Chapter XV is a challenge. There are one or two caveats but here are a few quotes culled from the chapter.

“Most women … are really too gentle to be good gardeners” p228

“No! It needs a man to plant dafodils.” p228

“… two women gardeners can seldom be friends” p229

“ … women, in all floral matters, resort to low and evil practices.” p236

Now, does this chapter nail the coffin to the book as a whole. Not for me, indeed, if you treat the outdated views, the sexist and misinformed proclamations as an example of how far we have come in the last 100 years, then one can enjoy it for what it is. I’d like to think that most readers would be able to laugh at the content and rejoice in the fact that the tide has turned irrevocably (if indeed there ever was a “tide”).

Now, does this chapter nail the coffin to the book as a whole. Not for me, indeed, if you treat the outdated views, the sexist and misinformed proclamations as an example of how far we have come in the last 100 years, then one can enjoy it for what it is. I’d like to think that most readers would be able to laugh at the content and rejoice in the fact that the tide has turned irrevocably (if indeed there ever was a “tide”).

In the spirit of balance, I have to point out that Mr Nichols does offer a counterbalance in the form of one or two women gardeners who, in his opinion, buck the clear trend.

I rarely address much in terms of dislike when it comes to book reviews, primarily because usually, my less than positive feelings about a particular book amount to nothing more than niggles. There was nothing that I vehemently disliked about this book, however, there were elements that created within me, a sense of discomfort.

As the book wends its way through the development of the garden we get to know the author in more depth, I was slightly uncomfortable with the faux poverty that manifested itself from time to time e.g. “I cannot remember the time that my family was not poor … we could only afford one gardener” (p209). The confident and acerbic treatment of some of the characters within hinted at a sense of self-righteousness. From a psychologists perspective, I also felt that, underneath the whimsical, flirtatious exterior, there was a slightly darker layer of bitterness, partly fed by an evident sense of entitlement. This couldn’t help but dim my enjoyment of his gardening journey.

As the book wends its way through the development of the garden we get to know the author in more depth, I was slightly uncomfortable with the faux poverty that manifested itself from time to time e.g. “I cannot remember the time that my family was not poor … we could only afford one gardener” (p209). The confident and acerbic treatment of some of the characters within hinted at a sense of self-righteousness. From a psychologists perspective, I also felt that, underneath the whimsical, flirtatious exterior, there was a slightly darker layer of bitterness, partly fed by an evident sense of entitlement. This couldn’t help but dim my enjoyment of his gardening journey.

Would I recommend this book? Without a shadow of a doubt. It represents a snapshot in time across a panorama of politics, class and culture, the prevailing views of both plants and planting at the time of writing, and more. It provides clear evidence of the move from anachronistic and outdated sexism and patriarchal attitudes that permeated the time, to where we are now. He was undoubtedly, for better or worse, a man of both his time and his class.

Available on line (various outlets): £10 – £25

All sketches by Rex Whistler